Build it – and they will fall.

We’re often told that California housing costs will dip if more residences are constructed. My trusty spreadsheet’s peek into real estate and demographic patterns, however, questions the wisdom behind construction as a significant housing-cost containment measure.

You can begin with housing creation across the state, as measured by the California Department of Finance.

Related Articles

Fremont opens new affordable housing development for families

Group seeks to halt Menlo Park parking lot redevelopment with ballot measure

The Bay Area has hundreds of below-market rate apartments sitting vacant

714 is typical Californian’s credit score. How does that rank?

Gov. Newsom picks housing over CEQA in 2 bills aimed at speeding construction

The state’s housing supply grew by 556,000 during the past five years – a seemingly meek improvement above the 435,000 of the previous five years. But the statewide population decreased by 9,000 in the same time frame, according to state statistics. Contrast this slight dip with the 725,000 gain from 2015 to 2020.

The recent construction pace should have helped house hunters and apartment seekers. Yet, cost relief was almost nonexistent despite fewer Californians competing for residences.

House-hunt horrors

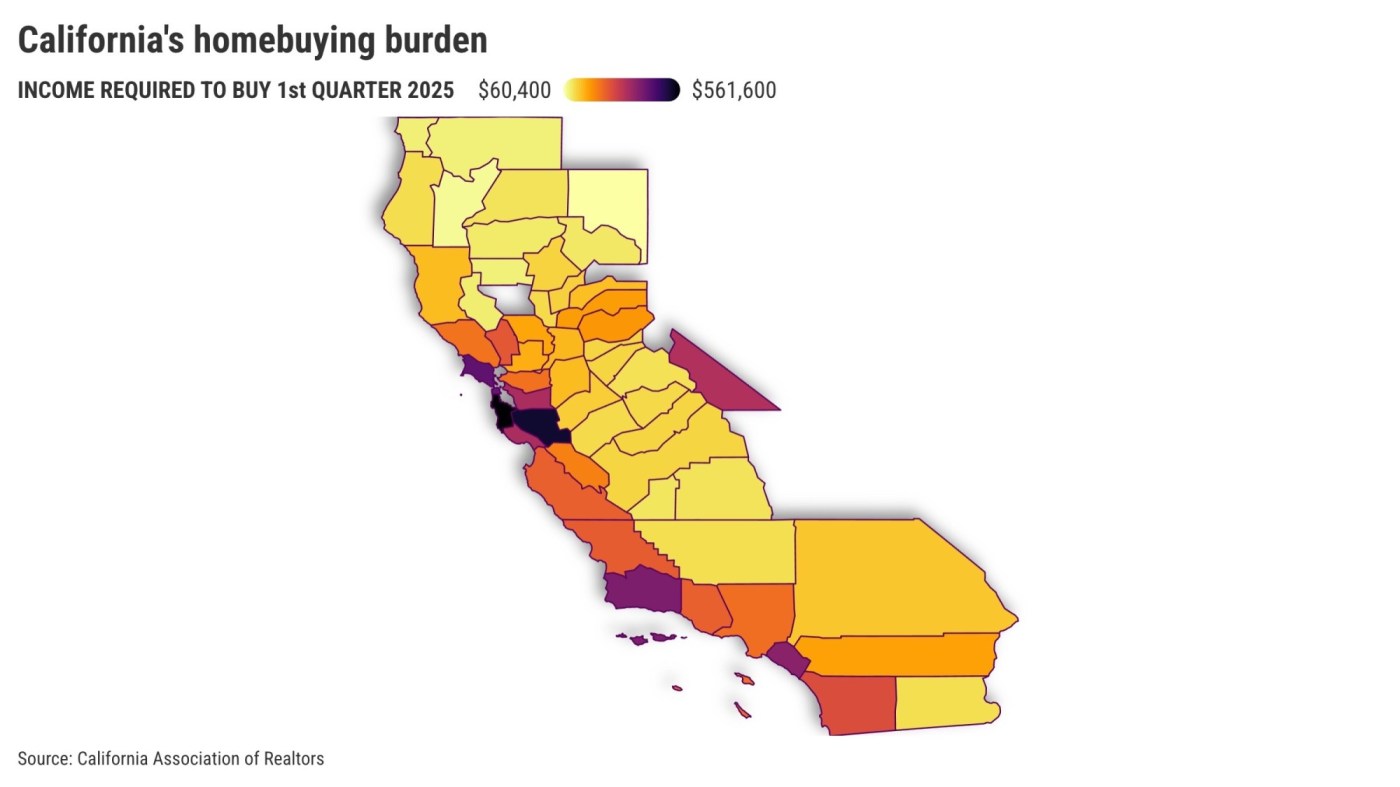

Think about a calculation of the annual income required to buy a typical California house. It’s nearly doubled in five years.

That’s comparing California Association of Realtors’ homebuying affordability data for the first quarter of 2025 to the final three months of 2019, just before the coronavirus disrupted the economy.

To start 2025, a minimum annual income of $218,000 was necessary to buy a median-priced home. This standard surged 82% since the end of 2019. The Realtor yardstick assumes buyers spend 30% of their income based on a mortgage with a 20% down payment, with an additional 1.4% of the purchase price going toward property taxes and insurance.

A significant challenge for house hunters was mortgage rates. They were 6.93% in early 2025, compared with 3.89% in late 2019.

And do not forget pricing. California’s median home sales price increased by 40% over the past five years to $846,830. Where did that demand come from?

Geographically speaking, Southern California is considered “cheaper,” according to this math.

The region’s house hunters faced a required income of $213,600 – up 97% in five years. That pay qualifies someone for the $830,000 median residence, which is 51% pricier than in 2019.

But those needs vary among the counties. Orange’s $373,200 requirement has increased by 129% in five years. Then there’s San Diego at $266,800, up 107%, Los Angeles at $222,000, up 83%, Riverside at $164,800, up 99%, and San Bernardino at $128,800, up 106%.

Across the Bay Area, salary demands are even more severe.

You’ll need $334,400 to buy – up 84% in five years. That gets you the $1.3 million median residence, up 41% since 2019.

By county, San Mateo’s $561,600 requirement was up 84% in five years. Santa Clara is at $520,000, up 112%, Marin is at $424,800, up 63%, San Francisco is at $418,800, up 33%, and Alameda’s $334,400 is an 88% jump.

Troubled tenants

Consider that California renters also face demands of six figures.

Contemplate rent data from Zillow, which tracked the stress on tenant finances in the nation’s 50 largest metro areas. California is home to five of the eight U.S. markets where incomes of $100,000 or more allow the rent check to remain at a manageable 30% of the local median income.

Start with the typical renter in the Inland Empire, who needs to earn $102,722 this year . That’s the eighth-highest burden among the 50 metros.

Worse still, this financial hurdle for Riverside and San Bernardino counties has expanded by 46% in five years. The only larger jumps nationally were in Miami (54%), Tampa (52%), and Providence, Rhode Island (51%).

Or ponder San Diego County, where its $122,810 threshold was the fifth-largest nationally. This financial burden increased by 41% over five years, the ninth-largest jump among the 50 metros.

In Los Angeles and Orange counties, the $118,958 threshold ranked No. 6 among the 50. The 28% jump in five years was No. 38.

In the San Jose metro area, $136,532 was the standard – the nation’s highest. However, this rent burden increased by only 13% over the five years.

That was the second-smallest advance, just ahead of the 9% increase in San Francisco. Its $124,267 income threshold was the fourth highest nationally.

What’s going on?

Well, there’s “luxury” housing construction, investors, short-term rentals, vacation homes, and poor policy decisions to debate another day.

Instead, focus on my real estate mantra: “Jobs. Jobs. Jobs.”

A modest California hiring spree provided numerous workers the means to afford the pricier housing – whether owned or rented.

Statewide, 520,000 jobs were added in the last five years – but that was far slower hiring than the 1.9 million jobs created in the previous five years.

And wages decidedly perked up.

Over the past five years, Southern California bosses paid 28% more – the biggest hike among 15 U.S. job markets tracked by the federal Employment Cost Index. Raises totaled 19% during the previous five years.

In the Bay Area, 22% wage hikes from 2020 to 2025 ranked No. 10 nationally, representing an increase from 17% for the previous five years.

Remember, the pandemic made roommates unappealing. And these paycheck pops motivated others to strike out on their own. Both trends created housing demand despite stagnant population growth.

That’s why the typical California household had 2.76 people in January 2025, down from 2.86 five years earlier. All 58 counties had a dip in housing density.

Not alone

Exploding housing burdens aren’t just Golden State madness.

There’s the $103,600 needed for a U.S. house purchase. This requirement has increased by 92% over the past five years. It buys an American a median residence worth $402,300, which is 46% pricier than in 2019.

And a typical U.S. tenant must earn $80,949 to keep the rent at 30% of income. That burden grew 35% in five years.

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at [email protected]