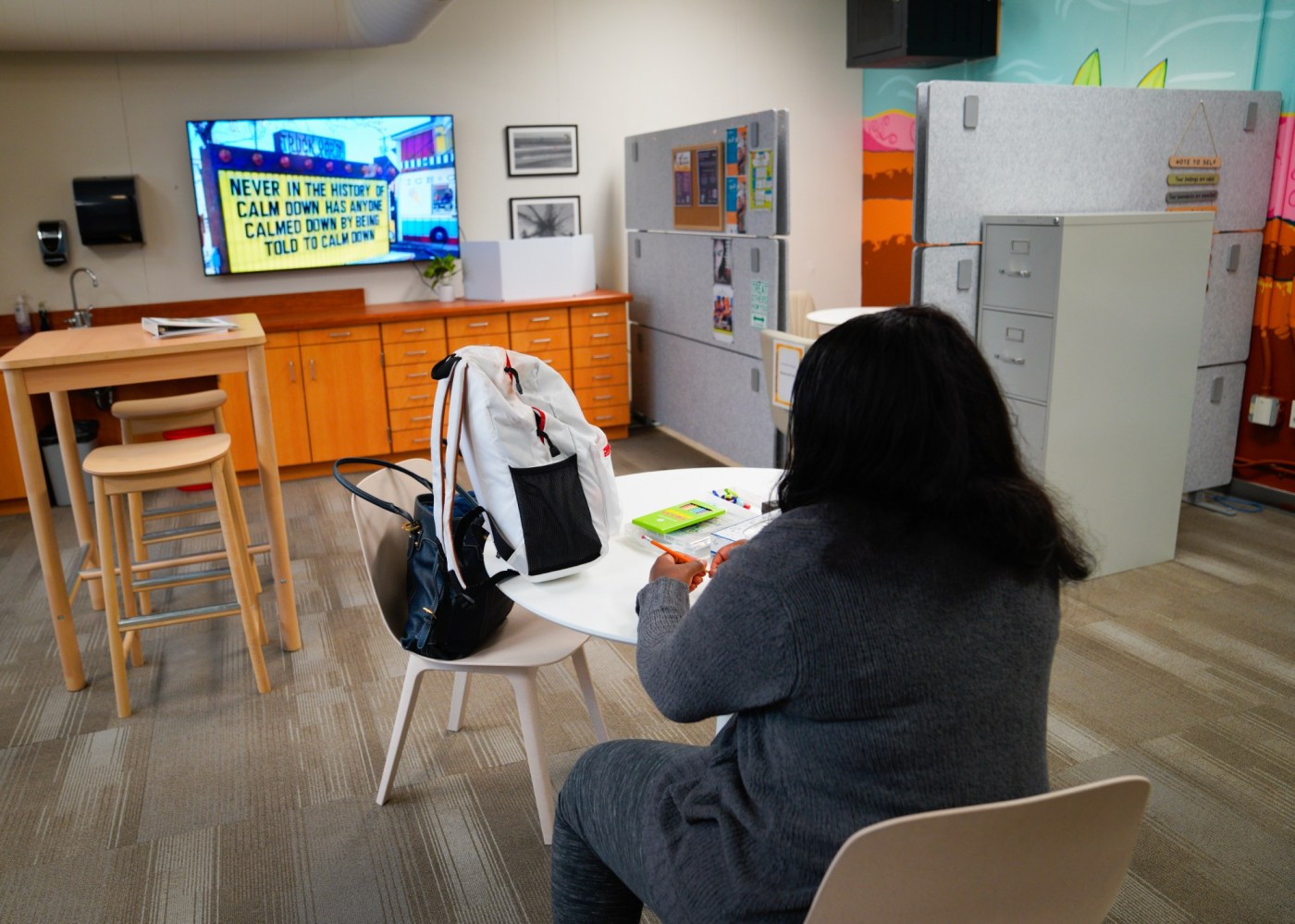

When a student comes into the wellness center at Oceanside High School, clerk Emily Clement can immediately tell if they want to talk.

“If they want to chat, they do two things: They’ll either sit in one of those chairs right there, or they’ll sit in the other barrel chairs,” she said. “Nobody that wants to talk sits at tables.”

Related Articles

Hundreds of tech, biotech, oil, school workers lose Bay Area jobs

New facility designed to ground Cupertino, Sunnyvale students in robotics

‘It’s absolutely critical’: West Contra Costa Unified eyes tax renewal

Opinion: Eight former Oakland school board members say students are casualties in teacher-union political power grab

‘Hero’ gamer thwarted a mass school shooting being planned in Northern California town

If a student needs time, she gives it to them. She invites them to make themselves at home, points them to the adult coloring books and puzzles. Often, after they’ve had a break, they might start talking — sometimes with her, sometimes with a group.

Sometimes they’ll request a counselor or social worker; other times, they’ll ask for a mentor to help them deal with a conflict.

Down the hall, there’s a food pantry — donations are delivered on Wednesdays — and a clothing closet with a range of options, from when a student finds themselves needing new pants during the school day to a rack of prom dresses.

The school’s wellness center, like its new counterpart at El Camino High, is part of the Oceanside Unified School District’s ongoing work to develop healthy relationships between its high schools’ staff and students and to improve how it administers discipline, and ideally to intervene before it becomes necessary.

That effort has also involved working to build student-teacher relationships, offering alternative forms of discipline, training educators on implicit bias implicit-bias and using restorative-justice coaches to help improve conflict resolution.

Administrators credit that work with a steep drop in student suspensions in just the last few years, and a growing number of school-level mediations. So far this school year, the district has seen only one third as many student suspensions as it did three years earlier.

At Oceanside High, suspensions have dropped even more dramatically, down to just 57 this school year from 323 three years earlier.

Emily Clement talks about the clothing closet at Oceanside High School. (Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

At the core of that work, said Principal Skyler Garrahy, is developing school culture by becoming a bigger presence in the community and gaining students’ trust.

“They see me walking my dog,” she said. “If they see me at restaurants, they see me as a real human being.”

That’s one of the first things she tells new staff when they join. But she also wants them to get to know the students better.

They’ve worked to get to know the students personally and go to events. She said they have started having celebrations for grades and attendance or “just being a good human being.” They have also started doing after-school events, like video game clubs.

And she credits their work to build those relationships with the improvements she says they have made in recognizing students’ needs — when they need to talk, when they need something to eat.

“I think that’s what’s really been able to make that number drop, as far as our discipline on our campus — because we have really doubled down on building culture,” she said.

The district has also focused on overhauling its discipline structure, explained Jordy Sparks, the district’s executive director of diversity, equity, inclusion and student supports. The district gives options of both traditional suspensions and in-school alternatives, with parental permission.

There’s still work to do to educate families about the alternatives. At times, Sparks said, families can think they let students get away with misbehaving, and schools need to show there are still consequences.

“It can be a little tricky and controversial, because people think that kids aren’t being held accountable,” he said. But, he added, “we can hold students accountable but do it in a compassionate way, and do it in a way that allows them to remain connected to school.”

Some parents say they would rather their children serve their suspensions at home. But there’s a reason Oceanside Unified often prefers not to.

“We want to teach them the skills — and it’s hard to teach them the skills when they’re at home and not in school,” Sparks said.

And since suspensions can disproportionately affect boys of color, the district is also working to train educators on implicit bias. This year, at both Oceanside High and districtwide, boys were suspended nearly three times as often as girls.

“We all operate with some sort of bias,” Sparks said. “But when the data shows that it’s impacting certain groups of students disproportionately, we have to do something about it.”

The wellness center at Oceanside High School is safe place where students can unwind and get references for campus student support groups. (Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The district has also been working with restorative justice coaches.

Rather than mete out a traditional suspension, the school will send a student to a separate program for a day where they work with a trained practitioner and teacher to reflect on their decisions, work through challenging situations and learn skills to navigate tough situations.

Oceanside High has also used mentorship programs and QR codes to let students ask for help through its wellness center. Now, he says, many more students are asking for conflict resolution before a confrontation or fight can happen.

The school has dealt with conflict resolution especially well, Sparks added. And Garrahy said the discipline reevaluation and training have already improved school practices.

To Clement, it’s important for staff to be calming presences and create meaningful community partnerships not only to help students now but to support them later in life.

“They’re going to graduate, they’re going to leave here and — if they’ve learned to open up in a constructive way to their peers — then they’ll continue to get the support that they need,” she said.