Dana Point surfer Scott Muir tucked into a deep barrel in the Oceanside surf, his surfboard and body disappearing into the wave’s cavern of ocean water.

A nearby surfer, Judah Ely, waited for the surfer to exit the wave, ready to cheer the ride. But Muir was gone, only his surfboard left floating on the ocean’s surface. Muir’s head had slammed onto a shallow sandbar, his body instantly going numb. He remembers the sound of cracking, his neck breaking. He tried to move, but his body simply wouldn’t, he said.

Related Articles

Santa Cruz surfers Alo Slebir, Wilem Banks earn wins at 25th annual Big Wave Challenge Awards

Santa Cruz surfer’s epic ride at Mavericks was largest of the season, but fell short of record

Santa Cruz surfer seeks world record for epic Mavericks wave ride

Photos: Annual World Dog Surfing Championships

Doug Haut marks 60 years of shaping surfboards with commemorative anniversary line

It was during a recent hurricane swell, and the waves were pumping and powerful, the current strong. Muir was fully conscious, trying not to panic, as a first wave tossed his body, then the second.

As the third wave pounded his limp body, Muir said he started sucking in sea water, his mind fading out. Then, a pair of hands grabbed him and brought him to the surface, pulling his body to shore.

Luckily, Muir had made friends who looked out for him during his surf session.

Sharing the stoke

Muir and friend Dan Pierson had chased the big waves sent by Hurricane Narda down to Oceanside, finding a secluded spot with few people out in the water.

The surf session started with an exchange with two other surfers in the water, Ely and friend Thomas Alspaugh, the wave riders jockeying for position, paddling deeper than one another, competing for the best waves.

“A bit of competitiveness, rather than camaraderie,” Muir recalled.

Ely dropped into a barrel, his sharp surfboard nearly hitting Pierson. But instead of prompting an argument — as can happen between surfers competing for waves — the close call brought the wave riders together.

Ely paddled by to apologize and Pierson, instead of scolding the younger surfer, responded with, “That wave was insane, that was so cool to see you send it!”

Completely helpless

A set showed up on the horizon and Muir told Ely to go on the first one. He took the second wave, crouched down into what would have been the wave of the day. But instead, his body tumbled inside of the barrel.

“It threw me down headfirst and I heard this crunch,” Muir said. “I couldn’t move anything. I was completely helpless.”

Ely recalls seeing Muir getting deep inside the barrel, going backside on the left-hand wave. He even recalled letting out a little “yeeew” as he watched Muir get pitted.

He went to duck dive under a wave and when he came back up, Ely said he looked around to give Muir props for his deep barrel.

“I’m looking for him and don’t see him come up, I just see the board,” Ely recalled. “It took me a few seconds before I knew the severity. I was watching, waiting for him to come up and thought, ‘It shouldn’t take this long.’”

Then, he glimpsed Muir’s shoulders and the back of his head, peeking above the ocean’s surface.

“This is bad,” Ely remembered thinking.

“I started swimming over to him, a wave hit him. He was only visible for one to two seconds. He never popped up again after that wave,” Ely recalled.

It took about half a minute for Ely to reach Muir. Ely searched around underwater for Muir’s body, the water brown and murky from sand churned up by the strong surf, he said. Then Ely found Muir, hauling him to the surface.

“I was trying to keep my head above water, but most importantly, his,” Ely said.

Alspaugh saw Ely holding up Muir’s body and called out to Pierson and other surfers nearby to help, quickly flagging down lifeguards.

Alspaugh has been a junior lifeguard instructor for the last three summers at Salt Creek Beach with the OC Junior Guards Program, so he knew how to stabilize Muir’s spine once they were on shore.

“We ripped off our leashes and started holding him in the right position to put the spinal board under him,” Alspaugh said. “It was pretty instinctual. Because of what’s been programmed into me because of the junior lifeguard program, I knew what to do.”

The first thing Alspaugh and Ely said they did after they watched Muir be taken away in the ambulance was contact their church with a request for prayers.

“He has a wife and kids, and he’s the breadwinner,” Alspaugh said.

When they heard a surgery on Muir’s broken spine had gone well and he was starting to regain movement, the teens were “super stoked,” Alspaugh said.

Muir said the positive attitude everyone brought to the beach that day set the stage for his rescue.

I’m completely convinced the stoke and goodwill in the water is why (Ely) was looking for me,” Muir said. “That’s the reason he got me. Having good vibes in the water. It’s easy to forget that surfing is playing at the end of the day. That’s the only reason any of us are out there, to play in the water.”

Just last month, Muir raised $5,000 and joined more than 130 paddlers who crossed the Catalina Channel to Newport Beach for the 10th annual “Ben Did Go,” a 30-mile trek that raises awareness and funds for ocean safety — never imagining a few weeks later, he would be the one needing to be rescued. The channel crossing is in honor of Ben Carlson, a Newport Beach lifeguard who died during an ocean rescue.

“It’s absolutely devastating to hear what happened, and all we can do is help support him and his family anyway we can to get the word out about his GoFundMe,” Ben Carlson Foundation board member Tim Burnham said. “He’s got a long road of recovery.”

Muir said he is thankful to the people who have reached out, sent prayers and given donations to help his family stay afloat while he undergoes intensive rehabilitation in Colorado.

The injury is “incomplete,” meaning his spinal cord was not severed, and he’s starting to regain small movements in his legs and arms, he said, and even sat up and stood for a few seconds on a recent day.

“I’m feeling optimistic and super loved,” Muir, an Air Force veteran and pilot, said.

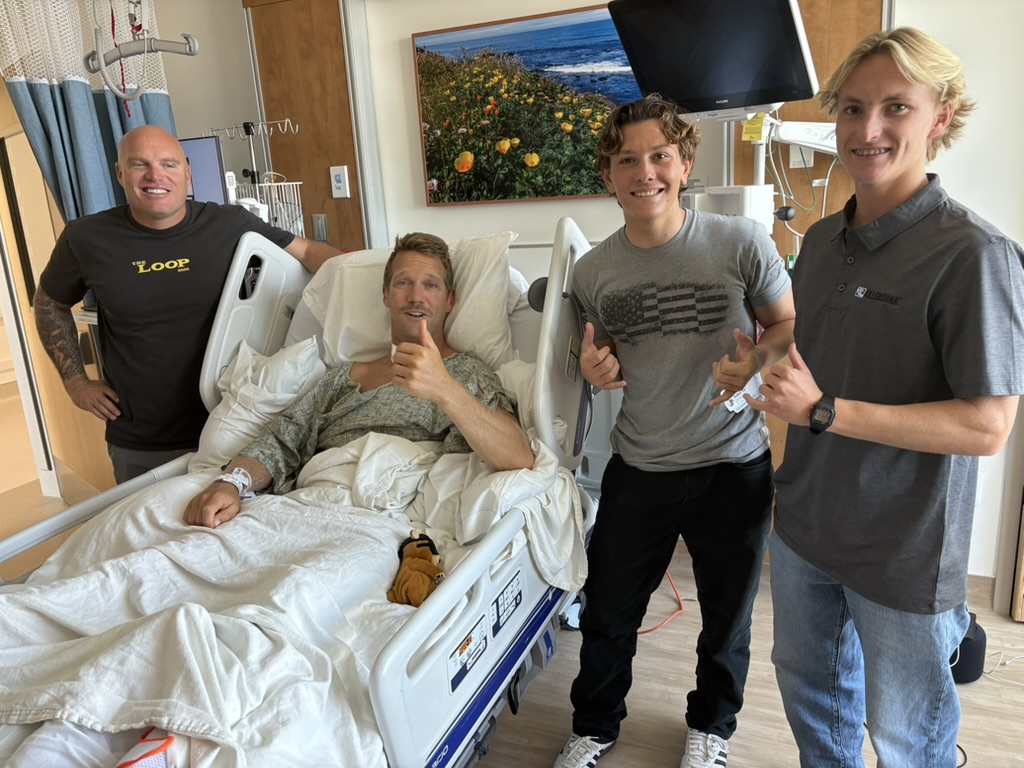

Muir is especially thankful to his rescuers, he said, who reunited with him before he left the hospital.

“It’s hard to even describe just how wonderful it was to see those kids, those men,” Muir said. “It goes so deep now with those boys, they are more than acquaintances, they are family now. We are forever linked and I have their back forever, that’s for sure.”

For Ely, it was a lesson to be more friendly to people, especially while surfing.

“It’s been heavy on my heart for a long time. The surfing culture is very hostile and aggressive, and we don’t treat each other with love,” he said. “At the end of the day, you’re competing for waves, but you’re both doing something you love.”

It’s a lesson that can be applied outside of the water, too, Muir said, at the grocery store, gas pump or even when someone cuts you off in traffic.“Just smile.”

“That’s what I love about this whole thing, human kindness,” he said. “It’s pretty cool.”