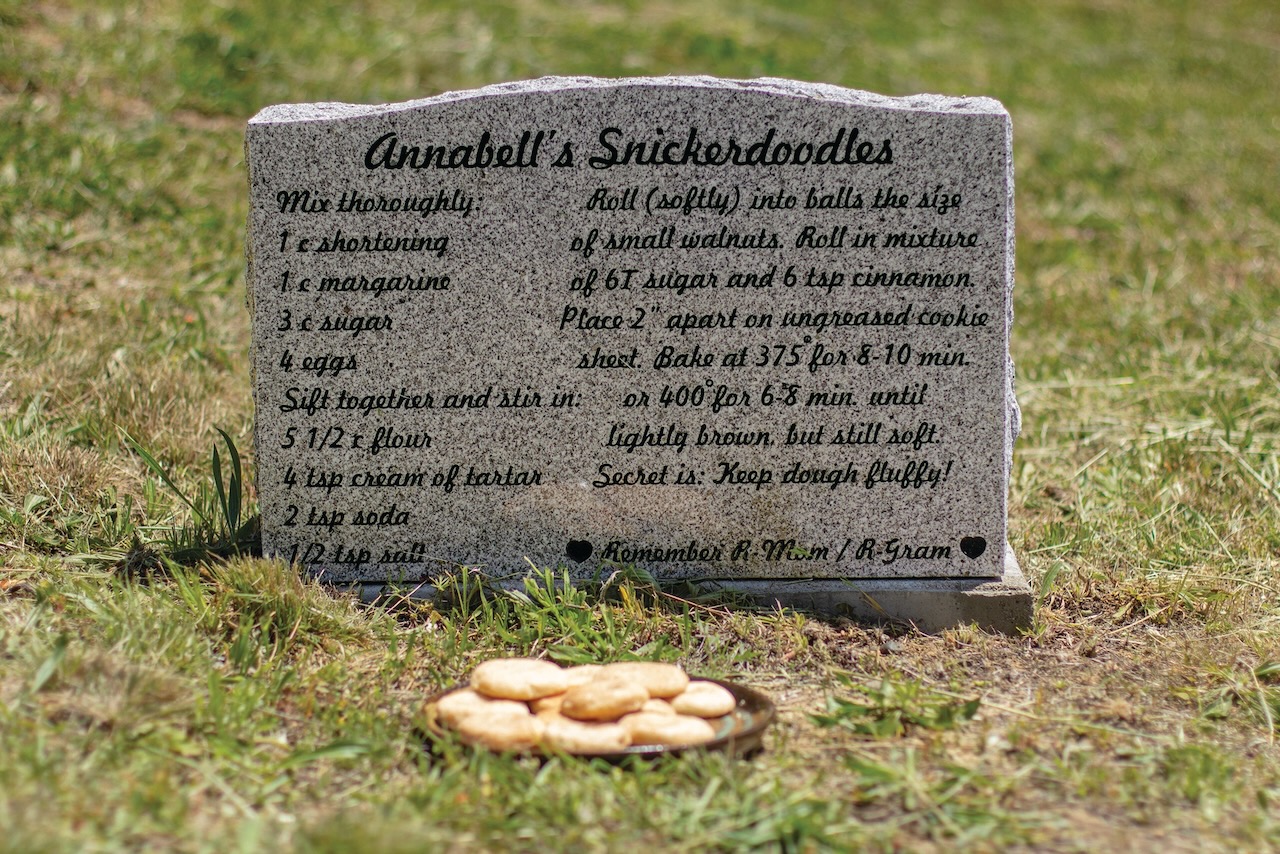

Who’d have guessed that the place to find a killer spritz cookie recipe would be inside a cemetery?

But that’s just where Naomi Odessa Miller-Dawson’s cookie recipe lives, etched in stone at her final resting place at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery.

Related Articles

Q&A: Samin Nosrat on her new cookbook ‘Good Things’

Need inspiration for fall cooking? Grab these 3 cookbooks

Recipe: Vegan watermelon seed and cashew ricotta

With her new cookbook, vegan cheese pioneer hopes to democratize food

The Bay Area culinary club that’s eating its way through history

When archivist Rosie Grant, who was was completing an internship at Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., learned about this recipe on a gravestone back in 2021, she decided to bake the cookies and share a video of the experience on her TikTok account, @ghostlyarchives. Comments poured in, and she learned that there were gravestone recipes scattered across the U.S.

So began her quest to cook the recipes and learn the stories of the people behind them — a project that eventually yielded an entire 40-recipe cookbook. Grant’s book is more than a cookbook copying over these recipes etched in stone, however. It also explores the intersections of food, legacy and memory, while providing background information and missing details to enable anyone to cook these recipes at home.

We recently caught up with her to learn more about her brand-new cookbook, “To Die For: A Cookbook of Gravestone Recipes” (Harvest, $26), which came out Oct. 7.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

“To Die For” cookbook author Rosie Grant is the creator behind @GhostlyArchive, a TikTok account she started while an intern at Congressional Cemetery. After finding and cooking a recipe she found on a tombstone, she kept discovering more recipes and made a cookbook out of the collection. (Courtesy of Jill Petracek)

Q: What inspires someone to put a recipe on their gravestone?

A: A lot of modern gravestones are very personalized. Maybe 200 years ago, or even 100 years ago, there would be one carver who would make a bunch of templated stones, and then just add someone’s name and dates. It was pretty standardized. Nowadays, it’s a blank slate that you get to fill in based on what was important to you. That might be a recipe, a music quote or even a call number to someone’s book in the library or a reference to their dogs. In a lot of cases shared in the book, these people were home cooks. They hosted the holidays. They loved food. There are a lot of central community figures, the ones who would do the volunteer event, host Christmas or Thanksgiving or make people’s special birthday treats. They used food to show love and celebrate other people.

Q: Were most of the recipe gravestones you found modern?

A: Pretty modern. The oldest one is from a gentleman, Joe Sheridan. He is attributed with inventing Irish coffee. The story goes that Joe was in Ireland, and this plane came in with a bunch of travelers. He was basically the airport chef, and it was raining. All the passengers were cold, and they asked Joe to make something to warm them up. So he made them his hangover cure, Irish coffee.

Joseph Sheridan, known for popularizing Irish coffee in the U.S., was a chef at the Foynes Airport in Ireland in the 1940s who introduced a plane full of stranded passengers to his hangover cure. Word spread to travel writer Stanton Delaplane, then the team at Buena Vista Cafe in San Francisco, who worked with Sheridan to perfect the recipe. (Courtesy of Jill Petracek)

There was a travel and food writer named Stan Delaplane, who, when he went back to New York, wrote about the Irish coffee, and it became this whole thing. In San Francisco, the Buena Vista Cafe heard about it. They flew Joe to San Francisco, and he basically re-created it with the restaurant owner and with Stan. And now the Buena Vista is considered the birthplace of Irish coffee. He’s buried in Oakland, and his gravestone says he gave the gift to his world, his Irish coffee recipe. And so he doesn’t even have the recipe written on it, but I got permission from the Buena Vista Cafe to include it.

“To Die For: A Cookbook of Gravestone Recipes,” by Rosie Grant (Harvest, $26) showcases 40 recipes carved into gravestones, and tells the stories of the people behind them. (Courtesy of Harvest)

Q: You went and visited all of these gravestones and interviewed family members. What were some of the things you learned while doing this research?

A: The first recipe I just thought was a one-off. But it was during the pandemic, so I thought I would try to make it, because, why not? So I cooked it, and I posted about the process, and things kind of exploded overnight. People were sending all these messages, asking lots of questions, thinking through what they would put on their gravestone if they had a recipe, or even talking about people in their lives who had passed away and the recipes that they cooked to remember them.

After I learned there were others, I made a big Google doc and map, and I started pinning where these folks are buried. I used Find a Grave, which is like the Wikipedia of gravestones and obituaries. The obituary listed out their next of kin, so from there, I would reach out to friends and family. I would send them a note. Sometimes I would just contact as many people as I could find. I would get email addresses that bounced, or in one case, I messaged this one woman on Facebook every six months for two years and later learned she’d been dead for four years.

The families have all been so lovely. It’s a fine tightrope to talk to people who have lost someone, and I wanted to be thoughtful about what they wanted. Some people just wanted to communicate via email or Instagram messenger because it hurt to talk about.

I also had to test the recipes. Usually, the first time, I would make it extremely wrong, reading it directly from the gravestone. And then I would do more research. I would meet with the families, and in some cases, cook with them. I would learn the tools that they would use.

Q: Some of the recipes were incomplete?

A: Yeah. I mean, an epitaph only has so much space. Most of these recipes are pretty simple. It’s not a lasagna or something that would take four gravestones to write out. But in some cases, the families got creative. So with Naomi, they didn’t put the instructions. They just put the ingredients to her spritz cookies. Another family had a handwritten recipe card lasered onto a woman’s gravestone, and they knew all the background details of how she would make her chicken soup. I, as a stranger, had to work with them to get the full recipe, and then that would be what ended up in the cookbook.

Q: Is it usually the person who dies or the surviving relatives who decide on the gravestone recipe?

A: It’s about half and half. In some cases, it was the relatives of the person who had passed away, trying to memorialize someone who was, in a lot of cases, larger than life and very giving. Sharing a recipe does more than just communicate, ‘She loved baking,’ or ‘She was a great host.’ It shares the tools for someone else to now partake in this tradition. It’s such an embodiment of who each of these people was.

Three of the recipes in the book are actually from women who are still alive. One is a woman named Peggy who lives in Arkansas. Her husband had passed away, and they were putting up their gravestone together, since they share a marker. On his side was his hobbies and things that he liked. Asking herself, ‘What do I want to be remembered for?’ for her side of the marker, she was like, ‘I’m really darn proud of my cookie recipe.’

When I met with her and cooked with her, all of these people showed up. I thought it would be for the novelty of some random TikToker making cookies. But they told me, ‘No, we heard Peggy’s making cookies. We drop everything when we know she’s making these cookies.’

In Ferndale, California, Christine and her husband are doing pre-planning and have already purchased and engraved their gravestones in a beautiful cemetery. His says, ‘I should have listened to my wife.’ And hers says, ‘Yeah, look where we ended up.’ Her carrot cake recipe is on the back.

Q: How has this project changed how you reflect on death?

A: My parents are both ghost tour guides. We talk about cemeteries all the time, and we love a good ghost story. But when it came to the actual death side of things, I hadn’t been aware of the death-positive movement, the idea that it’s healthy to talk about death, loss and our own mortality.

Where do you look for the people you’ve lost? There’s still so much of them with you, and it shows up in a lot of really joyful ways. For me, it’s been a very positive side to something that I personally found really scary.

Q: Anything else?

A: If anyone knows of any interesting gravestones, I’m always all ears.

Details: Follow Rosie Grant on TikTok at @ghostlyarchive and Instagram at @ghostly.archive. Her cookbook, “To Die For: A Cookbook of Gravestone Recipes” (Harvest, $26) is out Oct. 7.