Hoping the Federal Reserve will cut the interest rates it controls fits the “be careful what you wish for” conundrum.

There’s a good possibility the nation’s central bank will lower its Fed Funds rate – what banks pay overnight – at its next meeting Sept.17. Federal Reserve officials have acknowledged that a softening business climate may need help, overriding concerns about another bout of painful inflation.

Related Articles

Which California workers earn $100,000-plus?

California consumer confidence hits 6-month high

California ranks No. 1 for unemployment. Again.

California consumer confidence rises slightly in July

Bay Area 2050 plan moves to next phase

But cheers for such economic assistance – and some observers, including President Donald Trump, think the cuts should be steep – should be tempered. Why? When the Fed hands out discounted financing, it usually indicates the economy is in trouble. Plus, the cheaper money isn’t an immediate cure.

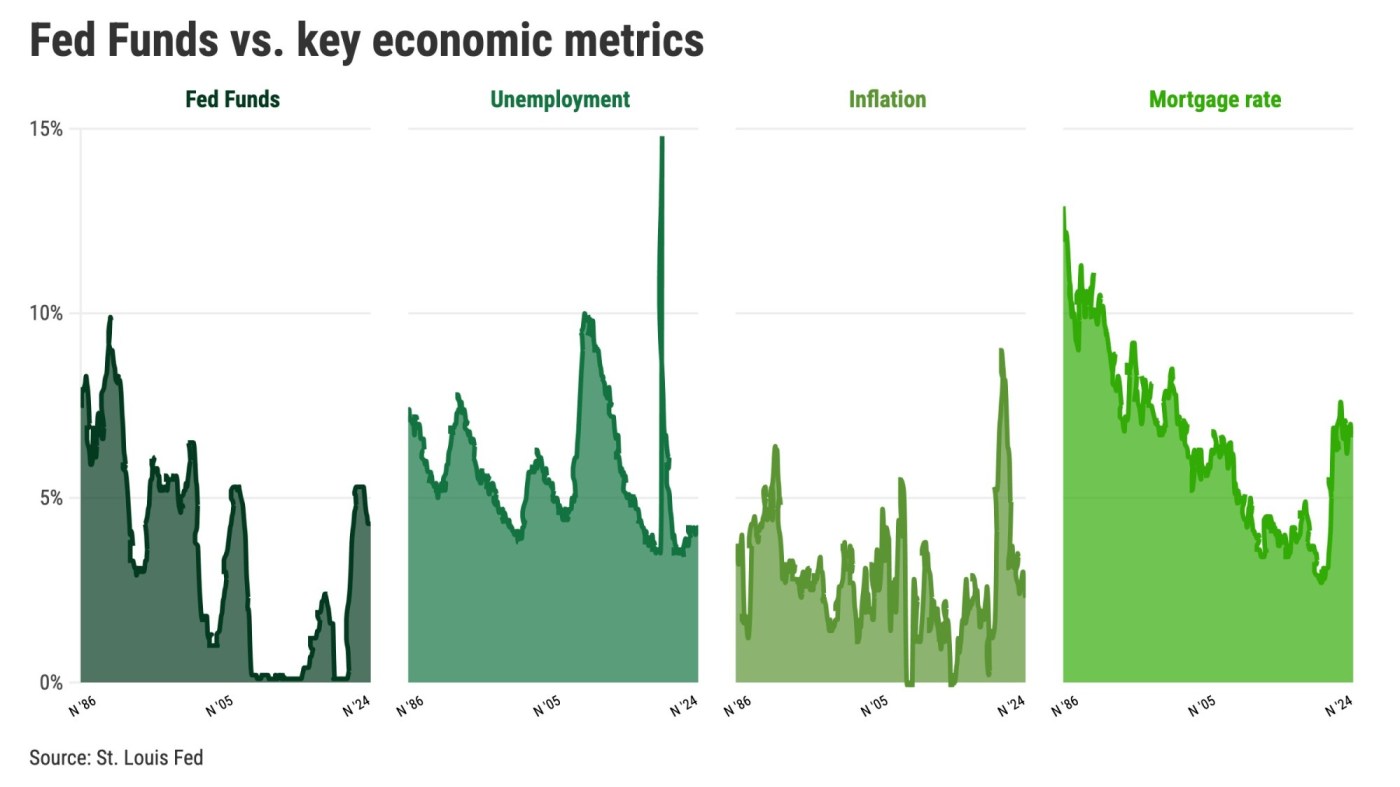

My trusty spreadsheet examined the relationship between Fed Funds and key economic variables over the past 40 years. The 480 months since 1985 were divided into three groups by 12-month changes in Fed Funds.

When the Fed was most active – the 160 months with the most significant cuts – Fed Funds dipped on average to 3.8% from 5.6% 12 months earlier. That’s a 1.8 percentage-point drop. And note that this rate has averaged 3.4% overall since 1985 and is currently at 4.3%.

To gauge the Fed’s economic impact, consider how 10 economic metrics performed when the central bank aggressively lowered its flagship rate. The metrics were ranked by how often they moved in tandem with Fed Funds.

Mortgage dips: Home loans typically get cheaper as the Fed’s slashing of short-term rates reverberates to longer-maturity financing. The 30-year rate fell to an average of 7.4% in the 12-month periods with the most extensive Fed cuts. That’s down from 8.1% in the previous 12 months but above the 6.5% 40-year average. Such declines occurred 88% of the time following significant Fed actions.

Bearish business climate: It’s likely to be weaker as the Fed tries to reverse business malaise. A Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank index of U.S. economic output shows 1.1% annual growth as large rate cuts get made, down from 2.7% in a year and a 2.7% 40-year average. This growth chill occurred 81% of the time.

Weak job market: Employment opportunities shrink. U.S. job counts fell an average of 0.2% in the rate-slashing periods since 1985, compared with 1.4% gains in the previous year and a 1.3% annual hiring pace since 1985. Job growth slipped 79% of the time.

More unemployment: The Fed’s job is to balance swings in the cost of living against joblessness. When the central bank is actively lowering rates, U.S. unemployment is usually rising. It averaged 6.3% after bold Fed actions, up from 5.4% the preceding year, above the 5.8% norm. This increased joblessness occurred 74% of the time.

Growing anxieties: Falling rates unnerve shoppers. Consumer confidence, as measured by the Conference Board, dropped at a 14% annual rate following big Fed cuts. Shoppers knew trouble was ahead, with confidence down 7% in the preceding year. This optimism yardstick rose 2% annually since 1985 but dipped 67% of the time after big Fed cuts.

Rate hikes down: Landlords trimmed the rate of rent increases due to the economic challenges. Rent nationwide, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, rose an average 3.7% in a year after large Fed actions since 1985 vs. up 4.1% the year before and a 3.5% historic norm. Smaller rate hikes happened 63% of the time when Fed Funds tumbled.

Inflation cools: Business slowdowns often dampen the cost of living because folks have less money to spend. The overall CPI rose just 2.6% in these heavy rate-cut periods since 1985, down from 3.3% the previous year and below the 2.8% 40-year norm. Such coolings were found 63% of the time.

Home gains slow: Price appreciation averaged 3.3% a year after noteworthy Fed cuts, according to a federal home-price index. That’s down from 3.5% gains the year before and the 4.8% 40-year pace. But note that such coolings occurred only 38% of the time after big Fed cuts. So the central bank’s pull on prices is unclear.

Stock gains slow, too: The S&P 500 stock index rose at an average 5.8% annual rate following big Fed moves, down from 7.9% in a year vs. a 10.4% 40-year norm. But such cooling occurred just 60% of the time after big Fed cuts. Again, falling Fed Funds haven’t been a grand predictor of Wall Street’s future.

Homebuilding slides: By the time the Fed is cutting, building permits are slumping. After the central bank acted, permits dipped at an average 3.1% rate – but that was better than the 4.4% drops in the previous year. But note this “improvement” in permitting’s direction occurred only 51% of the time after significant Fed action. So, the central bank’s impact on new home construction is basically a toss-up.

Simply put: It’s not happy days when the Fed is aggressively cutting.

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at [email protected]