SAN FRANCISCO — Dr. Gil Rabinovici, a leading neurologist at UC San Francisco, has examined “thousands, if not tens of thousands” human brains.

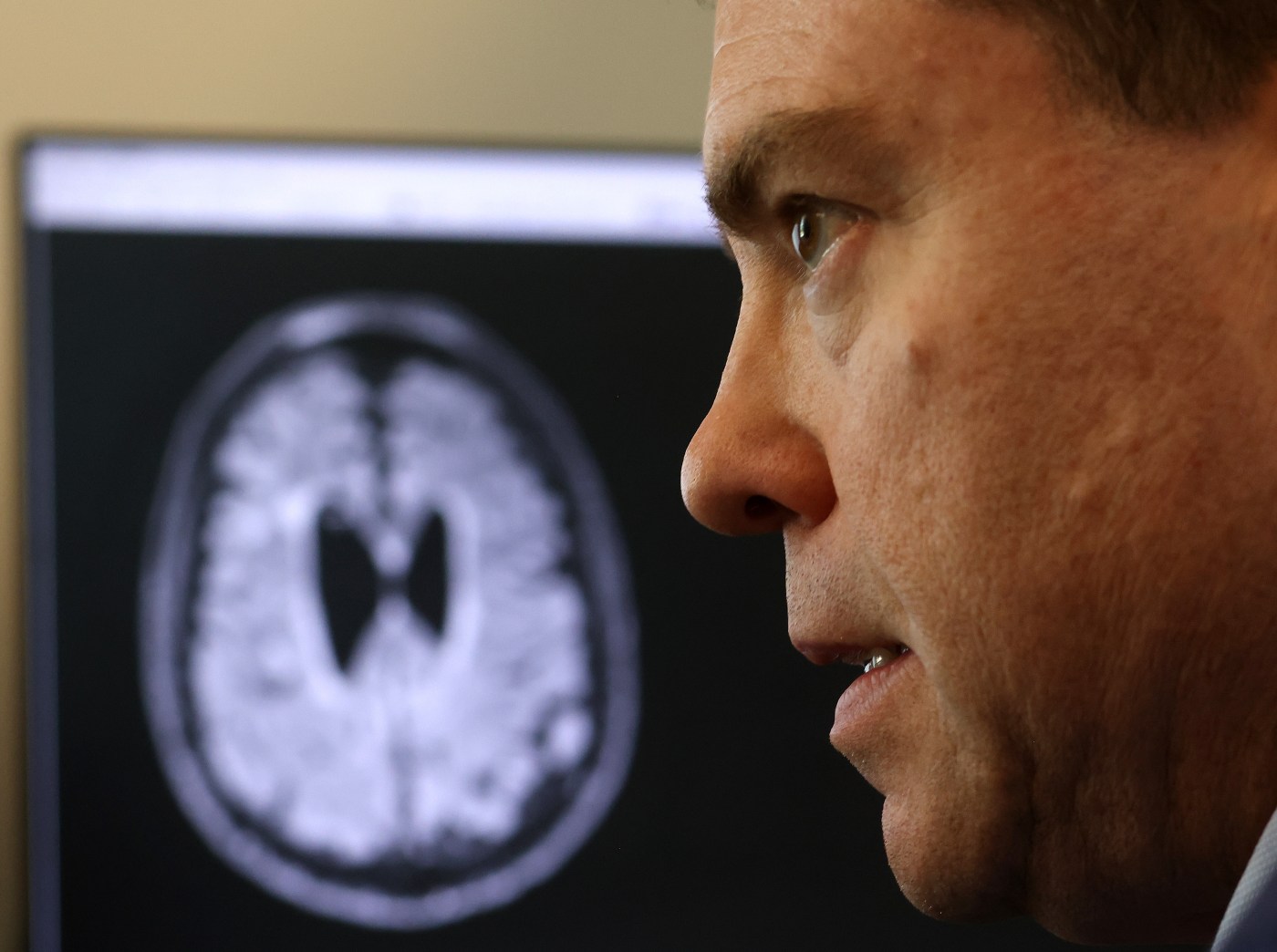

On a recent day in his ground-floor Mission Bay office, decorated with regalia of his alma mater, Stanford, and his hometown team, the Chicago Cubs, Rabinovici pulled up an image of one mind on his computer screen in the form of an MRI scan.

“Do you see all these white dots?” he asks, gesturing toward a small collection of specks sprinkled around the prefrontal cortex. “Yeah, that’s not normal.”

Brains are on the minds of more than just neuroscientists as football kicks off around California and across the country this week. From PeeWee to the pros, the sport is safer than ever, according to those who play it and coach it. Its brutal nature and long-term effects, however, are inescapable.

The sample belongs to one of 225 subjects in an ongoing trial at UCSF and four other sites around the country involving 150 former college and professional football players.

The dots on the scan could appear for a variety of reasons, Rabinovici says, but this brain has “a lot more of these than you would expect for their age” — the likely result of repeated blows to the head.

The question researchers are trying to answer: Is it also a sign of chronic traumatic encephalopathy?

Currently, the only way to diagnose CTE is posthumously, by taking a slice of brain tissue and dying it to identify the tau protein associated with the neurodegenerative disease.

The trial, the second phase of the NIH-funded DIAGNOSE-CTE project, only began in April, but researchers are hopeful that by the time it is complete, in June 2029, they could have a clinical diagnostic test for living people.

Dr. Gil Rabinovici at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center on Thursday, Aug. 21, 2025, in San Francisco, Calif. Researchers are working to devlop a diagnostic test for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in people living with the degenerative brain disease. (Aric Crabb/Bay Area News Group)

Paul Rosa, the head football coach at Santa Clara’s Wilcox High School, witnessed the deterioration of his uncle, a former boxer and football player, and knew before he got confirmation.

Luis Rosa died in 2020 and was posthumously diagnosed with CTE. According to Paul, his uncle built a comfortable life and a six-figure bank account in Southern California as a restaurant operator, “and then all of a sudden, about his early 50s, you could see his personality change.”

He suffered from constant headaches, battled depression and turned to alcohol. He died homeless, bouncing between family members’ houses.

“It was just like a switch flipped,” Rosa said. “To me, it was pretty obvious (it was CTE).”

The link between high-level football and CTE is well-documented, with the disease found in 345 of 376 deceased players who had their brains studied by Boston University in 2023.

The risk for those who didn’t play in college or the pros, though, came under the spotlight this summer, when a gunman targeted the NFL’s Manhattan office building, killing four people, including himself. He played football growing up in Southern California, but stopped after high school, and claimed to be suffering from CTE.

Another Boston University study sampled 152 contact sports participants who died before age 30 and found signs of CTE in 63 of them (41.4%), leading Dr. Ann McKee, the director of the Boston CTE Center, to warn: “We’re seeing the beginnings of this disease in young people who were primarily playing amateur sports.”

In the first phase of the DIAGNOSE-CTE trial, researchers attempted to identify risk factors and found a closer correlation between CTE and total years played than the number of concussions, indicating subconcussive blows can also be harmful.

“There is some data that suggests that starting football at a younger age puts people at higher risk,” Rabinovici said. “Most of the people that I know who are doing this research don’t let their kids play football at all.”

Rosa, entering his 11th season at Wilcox, encounters plenty of parents who won’t let their children play for his team. He raised two multi-sport athletes who went on to play football in college, and he said wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Especially nowadays, kids don’t do stuff that’s hard anymore,” he said. “Football is one of the throwback things where you work together as a team, it’s tough, you’ve got to work hard. As a parent, I wanted my boys to go through something that’s hard.”

Wilcox head coach Paul Rosa, shown here in a file photo, did not agree with a controversial delay-of-game penalty call that proved costly in Saturday’s CIF NorCal Division 2-A championship game at Twelve Bridges High School in Lincoln. Wilcox lost 28-27 after missing a last-second field goal. (Thien-An Truong for Bay Area News Group) Thien-An Truong for Bay Area News Group

He’s not alone.

While participation hasn’t returned to levels seen in the early 2010s, the number of boys playing high school football went up in the most recent national and statewide surveys after almost a decade of steady decline.

Many other sports, such as soccer, ice hockey, rugby and wrestling, present their own risk for head injuries, while new equipment and regulations make football a safer option than it once was.

In California, for example, high school teams are limited in the amount they can practice with contact, and helmets are required to be no more than 10 years old. This year, that eliminates any helmet made before 2015, when the state implemented a strict concussion protocol that requires student-athletes to receive clearance from a physician and sit out for a period of time.

Stanford University linebacker Tevarua Tafiti (11) takes part in football practice on Wednesday, July 23, 2025, in Palo Alto, Calif. (Aric Crabb/Bay Area News Group)

At the college level, “We’ve gotten much better at identifying the symptoms and educating our students, educating our coaches – anybody that could be around our student-athletes – what the symptoms of a concussion look like so that we can act as quickly as possible,” said Sarah Lyons, the director of athletic training at Stanford.

“In the last 15 years or so … I think the education has really changed. We’re taking things much more seriously now.”

During a recent practice, about half the Stanford players wore a Guardian Cap, a soft-padded shell for helmets that has been increasingly prevalent at NFL and college practices since it was introduced in 2015.

At Wilcox, the school recently invested in new helmets and ensures it has a trainer on the sideline at every practice, both upgrades since Rosa’s oldest son, Paul Jr., graduated in 2020.

“I’m interested to see, with these protocols put in place, what CTE looks like 10 years from now, 20 or 30 years from now,” the older Rosa said.

By then, Rabinovici and his team of about a dozen researchers at UCSF are hopeful they could have a way to detect the disease in living people. The next step would involve developing treatment and possible drug interventions through more trials, similar to breakthroughs surrounding Alzheimer’s, another degenerative disease caused by the build-up of tau proteins.

Dr. Gil Rabinovici at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center on Thursday, Aug. 21, 2025, in San Francisco, Calif. Researchers are working to devlop a diagnostic test for Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in people living with the degenerative brain disease. (Aric Crabb/Bay Area News Group)

The most promising method at the moment mimics one diagnostic test for Alzheimer’s, in which “tracer” molecules are injected into the brain and bind to the tau proteins, illuminating them during a PET scan. However, Rabinovici said the molecules used for Alzheimer’s “work a little in CTE, but they don’t work super great.”

That’s the cold reality of the research.

Of the 225 participants, 150 are holdovers from the first trial, which means they have been making near-annual visits for blood draws, brain scans and a battery of neurological tests since 2015. By nature of their profession, Rabinovici said, the group includes “some people who would be publicly recognized figures.”

Related Articles

Playing for Pop: Mt. Diablo running back dedicates season to late father

Bay Area high school football 2025: Week 1 preview, schedule

Did those who lit Mount Diablo High football field ablaze even know they did it?

Bellarmine football: Are admission standards too stringent to compete at top level?

Bay Area News Group high school football predictions: Week 1, 2025

It’s possible that the trials won’t produce a conclusive answer until the participants are dead, when current technology can confirm if they did have CTE and whether or not the diagnostic tests under study were accurate. Each participant agreed to donate their brain.

“That’s actually what was done to validate this technology in Alzheimer’s,” Rabinovici said. “The biggest problem that we have is that we don’t know who actually has the proteins in the brain. Because we don’t yet have a way of, even with all the symptoms and so on, of saying this person has CTE. So if we see a signal or don’t see a signal, is it because they don’t have CTE, or is it because the tracer isn’t working?”

In the meantime, the team sits down with the former players and their families and tries to repay them with feedback and resources. They set them up with neurologists, keep them up to date on their findings and keep their samples ready in case new tests become available.

While the participants tend to be “very curious” and “grateful for the feedback about what’s going on with them,” Rabinovici said, many have interests that go beyond their own brains.

“A lot of these players, their sons play football,” Rabinovici said. “They’re doing it for the next generation.”

Wilcox’s Brayden Rosa (2) tackles Sacred Heart Prep’s Maxime Morelle (46) in the 2nd half at Wilcox High School in Santa Clara, Calif., on Friday, Oct. 25, 2024. (Thien-An Truong for Bay Area News Group)