California’s self-designated deadline for achieving net zero emissions of greenhouse gases is 20 years away. But what is happening — or not happening — in multiple arenas now may determine whether that goal is met.

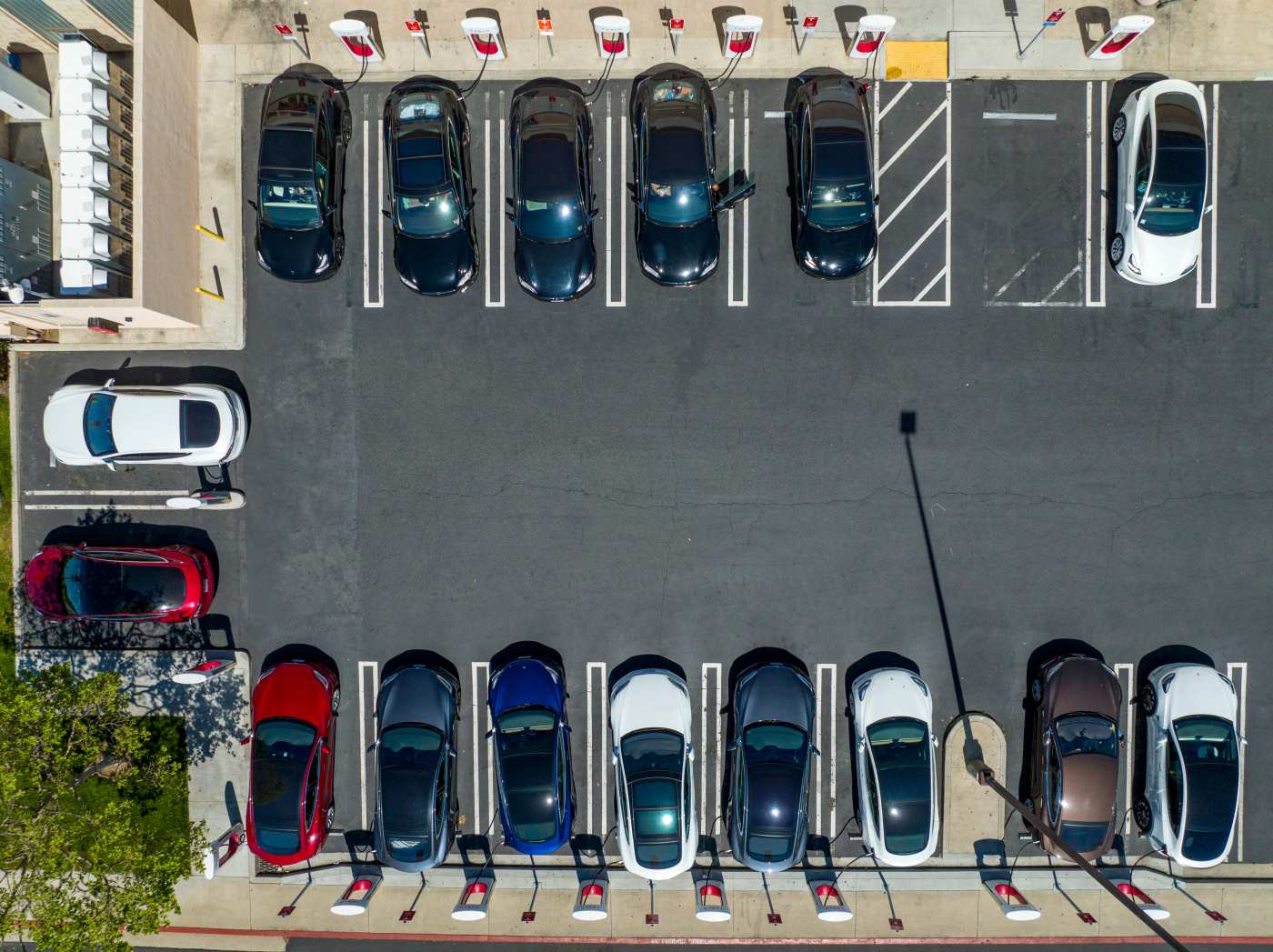

The largest single source of emissions is the nearly 1 billion miles that Californians drive each day. Accordingly the state has ordered that by 2035, all new cars sold must be zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). However, the state has interim goals and, so far, purchases of electric vehicles are falling well short.

This year’s goal was to be 35%, but sales have been running about 10 percentage points behind, compelling the Air Resources Board to push the 2026 goal of 43% off until 2027.

Meanwhile the Republican-controlled Congress, in response to pleas from automakers, has passed and President Donald Trump has signed legislation to cancel the state’s authority to deviate from national emission standards, effectively halting the zero-emission mandate.

“We officially rescue the U.S. auto industry from destruction by terminating California’s electric vehicle mandate,” Trump said. “And they’re never coming back.”

The state is challenging the new legislation in court, leaving the issue up in the air. However, even if the state’s waiver from federal standards is reinstated, the underlying issue of persuading Californians to buy electric vehicles would remain.

“To meet the revised 2027 target, California would need to increase ZEV sales by about 50% from current levels — rising from approximately 23% today to 43% in less than 24 months,” Rob Lapsley, president of the California Business Roundtable, notes in a recent analysis of the situation.

Related Articles

Police release search warrant in California state senator’s DUI investigation

Walters: California politicians ignore agriculture’s troubles but boost movie business

Evans: Don’t believe the haters. I’m from Arkansas. California is no failure.

Skelton: Big state budget questions linger about crime, Medi-Cal, Delta tunnel

Solar policy plan jeopardizes housing and energy affordability

Obviously, the state cannot directly force motorists to buy electric cars and trucks and can only offer subsidies or make it impossible to purchase anything other than a zero-emission vehicle. On paper, the legal onus is on automakers to meet the year-by-year goals, with hefty fines — thousands of dollars per vehicle — for falling short.

Another major front in the carbon war is the Air Resources Board’s “low carbon fuel standard” aimed at compelling refineries to lower the amount of carbon in gasoline.

While the board wanted it to take effect earlier this year, its regulations hit a snag in the Office of Administrative Law, which declared the regulations lacked the “clarity” needed to make them understood by those affected. The air board has rewritten some passages of the regulations, which are hundreds of pages long, and has indicated that they may take effect in July.

The big issue, at least to motorists, is how they will affect pump prices.

In 2023, the board estimated that adoption could immediately increase gas prices by 47 cents a gallon, and then “on average, from 2031 through 2046 the proposed amendments are projected to potentially increase the price of gasoline by $1.15 per gallon, the price of diesel by $1.50 per gallon and fossil jet fuel by $1.21 per gallon.”

The estimate generated a storm of media attention, and the board responded by refusing to put firm numbers on potential price effects, thus creating a guessing game that will end only when the mandate takes effect.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court declared last week that oil companies have the right to challenge the state’s emission regulations in court.

“The whole point of the regulations is to increase the number of electric vehicles in the new automobile market beyond what consumers would otherwise demand,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in the majority opinion.

“The government generally may not target a business or industry through stringent and allegedly unlawful regulation, and then evade the resulting lawsuits by claiming that the targets of its regulation should be locked out of court.”

The 7-2 decision implies that whatever else happens, the Supreme Court could have the last word, and it might not favor California.

Dan Walters is a CalMatters columnist.