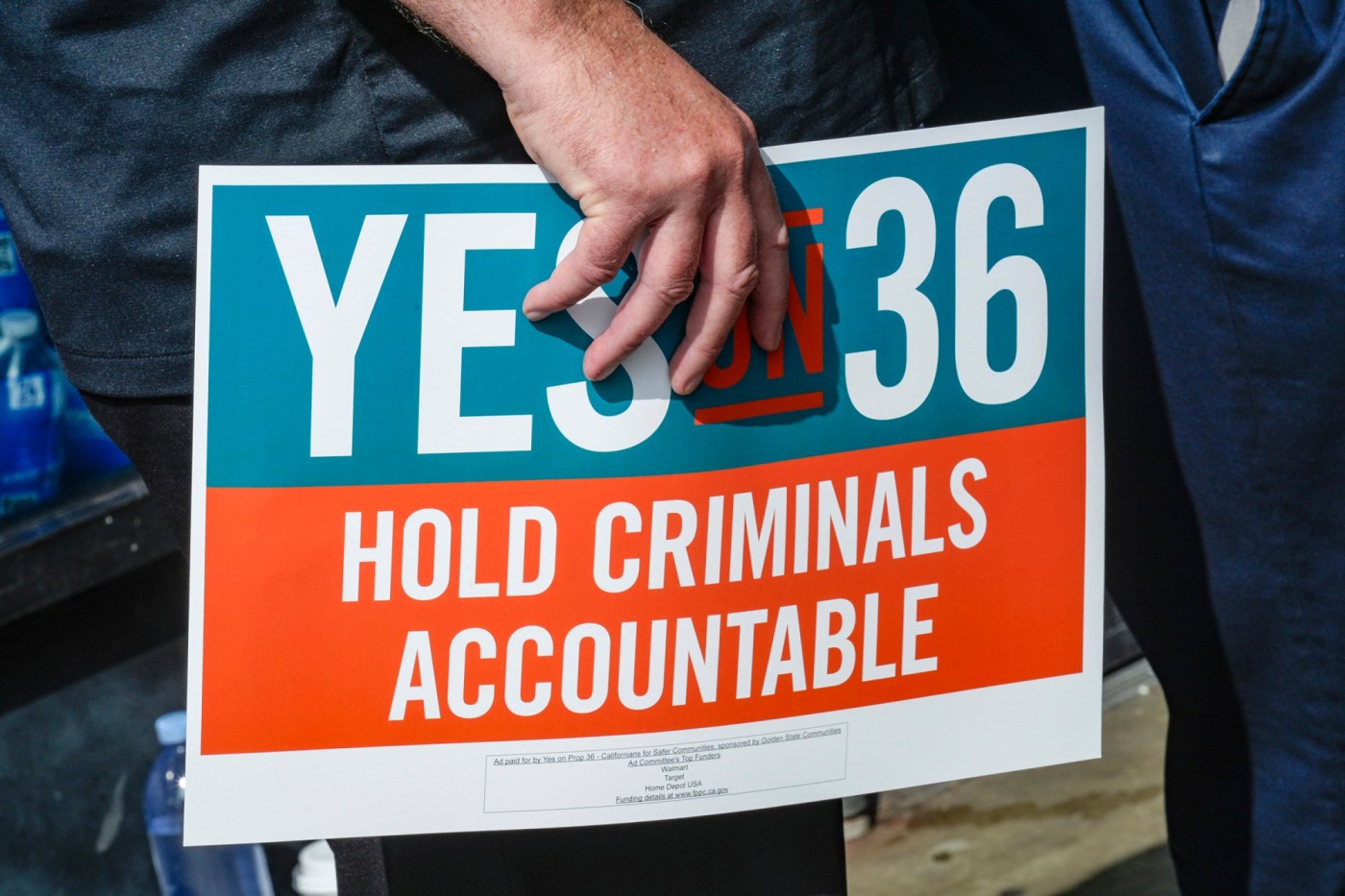

When California voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure to toughen penalties for low-level theft and drug crimes last November, it became law without any funding to cover the costs of locking up more people or ordering them into treatment.

Now, state and local lawmakers and Gov. Gavin Newsom are clashing over how to pay for it.

Proposition 36, which passed with nearly 70% of the vote, allows county prosecutors to bring felony charges against those caught using drugs stealing property of any value if they have been convicted of similar crimes in the past.

The new law also increases sentencing requirements for fentanyl dealers. And it gives repeat drug offenders the option to enter treatment and have their charges wiped away, or face up to three years in jail or prison if they don’t complete a program.

Newsom opposed the measure — describing it as an “unfunded mandate” — and chose not to include money for the proposition in his latest state budget proposal amid a $12 billion deficit, except for some additional funding to bolster the state prison system.

At a news conference last month, Newsom suggested that local officials who supported Prop. 36, and are now calling on the state to bankroll it, should come up with the money themselves.

“To say there needs to be a state bill to solve all their problems is not what the voters require,” Newsom said.

Last week, Democrats in the State Legislature agreed to set aside $100 million to phase in the measure. Half of the one-time funding would help expand treatment options, with the rest going to local courts and public defenders.

Lawmakers will now work with Newsom to try and reach a compromise for the finalized state budget, as the new fiscal year starting July 1 rapidly approaches. The governor’s office would not say whether Newsom would seek to strip away Prop. 36 funding from the budget.

State Sen. Scott Wiener, a Democrat from San Francisco and chair of the Senate’s budget committee, said voters’ unambiguous support for Prop. 36 means the state has a responsibility to help overburdened county behavioral health agencies prepare for a potential influx of patients — though not everyone charged under the law can be referred to treatment.

“It makes a lot of sense and we should have been doing this for years, providing more support to our counties and providing mental health and addiction treatment,” he said at a committee hearing earlier this year.

Republican lawmakers, who had requested $400 million for the new law, slammed Democrats’ proposal. In addition to more funding for treatment, they had called for money to help local law enforcement crack down on retail theft and drug trafficking.

The proposal “ignores the will of voters by underfunding Prop. 36,” Assemblymember James Gallagher, a Republican from Sutter County, north of Sacramento, said in a statement.

Local officials from both parties across California also say more funding is needed.

In a statement, San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan, a Democrat who campaigned for Prop. 36 — putting him at odds with Newsom — accused state lawmakers of ignoring voters’ frustrations over homelessness, addiction and public safety.

“The mandate couldn’t be clearer, and yet, instead of implementing the will of the people, Sacramento is attempting to sabotage it by refusing to fund the very solution voters called for,” Mahan said.

County officials across California contend the state needs to put forward $250 million to get the measure up and running.

“Counties can’t implement Prop. 36 without the full support of the state,” Graham Knaus, executive director of the California State Association of Counties, said in a statement.

According to the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, the law, which took effect in December, could raise state and local criminal justice costs by tens of millions of dollars to “the low hundreds of millions of dollars” annually.

During the first few months after the law took effect, one early estimate found prosecutors filed between 1,700 and 2,600 Prop. 36 felony cases per month, accounting for about 10% to 15% of all felony cases statewide.

But since district attorneys have broad discretion over bringing charges under Prop 36, the measure has played out vastly differently across the state.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, which analyzed the law’s roughly first 60 days, the number of charges brought per 100,000 residents ranged from 24 and 19 in Kern and Orange counties, respectively, to just two in both Fresno and San Francisco counties. Some county district attorneys, including those in Alameda, Contra Costa and Sacramento, brought mainly theft charges. Others, including those in Orange and San Diego, focused almost entirely on prosecuting drug crimes.

Related Articles

Bay Area mall security guard accused of assaulting teen

‘Dad went to war’: Vance Boelter tried three lawmaker homes before killing Minnesota Rep. Melissa Hortman and husband, charges say

Missing elderly couple and their pet at California nudist resort were killed over a hot dog

Appeals court upholds $1 million verdict in California middle school bullying case

California indictment unsealed after reputed cartel boss killed in shootout with Mexican police

Criminal justice advocates and public defenders have criticized Prop. 36, which reversed part of a voter-approved 2014 crime reform law, as a punitive measure that will lead to overcrowded prisons and jails and is poorly designed to help drug users succeed in treatment.

A Bay Area News Group investigation in April found that no one charged with drug crimes under the measure in Santa Clara or Alameda counties had been sent to treatment. Local prosecutors and other officials blamed a shortage of beds and the complicated legal process for referring someone to a program.

Advocates have also raised concerns the new law could slash dollars already earmarked for treatment as the state spends more to incarcerate people. In response, the state prison system updated its existing multimillion-dollar grant program to fund mental health and addiction programs for people charged under Prop. 36.

In a statement, Napa County District Attorney Allison Haley, who is also president of the California District Attorneys Association, said prosecuting the law is unworkable without more state investment in treatment and probation programs.

“We are very frustrated that the dollars allocated will not ensure the success of Prop. 36,” she said.