Last week, a state appellate court declared that a 2020 ballot measure to increase hotel taxes in San Diego is valid even though it did not receive the two-thirds approval that voters had been told it would require. The decision was the latest skirmish in a years-long political and legal wrangle over voting requirements for local tax increase proposals.

To begin at the beginning, in 1996, California voters approved Proposition 218 which, among other things, required two-thirds voter approval for local taxes designated for specific purposes. Proponents described it as an extension of Proposition 13, California’s iconic tax limit measure approved in 1978.

Related Articles

Newsom signs laws to stop flow from out-of-state puppy mills into California

Newsom signs bill to automatically admit qualified graduates to CSU system

Newsom signs bill that expedites Highway 37 project

Newsom vetoes bill restricting use of license plate reader data

Gov. Newsom signs two suicide-prevention bills

In 2017, the state Supreme Court hinted that while the two-thirds vote requirement applied to taxes proposed by local governments, it might not apply to those proposed by a citizens initiative, when enough signatures are collected.

Writing a 5-2 decision in a case called “Upland” because it dealt with a tax on marijuana sales in that city, Justice Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar declared, “Multiple provisions of the state constitution explicitly constrain the power of local governments to raise taxes. But we will not lightly apply such restrictions on local governments to voter initiatives.”

Tax proponents took the hint and began placing tax measures on the ballot via initiative, but often wound up in court. While some local judges applied the supermajority standard, others declared that simple majority votes suffice.

In 2020, the Supreme Court — in a roundabout way — ended the confusion by refusing to consider an appellate ruling that validated special taxes proposed by initiative and approved by simple majorities.

Last year, the California Business Roundtable and other groups that disliked the Supreme Court’s partial dismantling of Prop. 218 fired back with a constitutional ballot measure that would reimpose supermajority votes for special taxes proposed via initiative and place very tight restrictions on the legislature’s power to raise taxes.

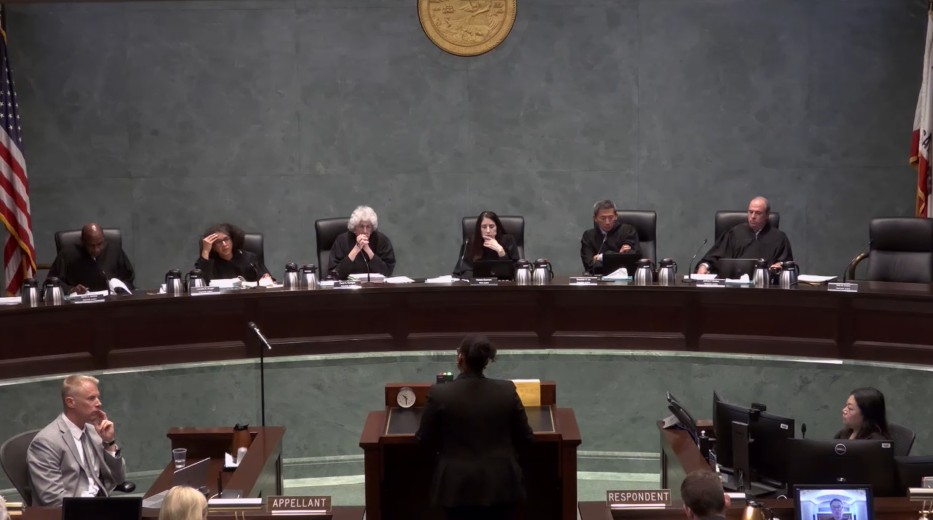

Once again, however, the Supreme Court interceded. It blocked the initiative, unanimously declaring that the Taxpayers Protection Act, as it was dubbed, would be a revision of the state constitution because of its restrictions on the legislature and therefore was itself unconstitutional.

“No speculation regarding potential future consequences is needed to conclude that the TPA is a revision on its face,” the court declared. “The measure would fundamentally restructure the most basic of governmental powers. The TPA would exclude the levying of new taxes from the Legislature’s control by requiring voter approval of all such measures.”

It’s against this background that the battle over hotel taxes in San Diego has been waged. Local leaders sought the increase largely to finance expansion of an already cavernous waterfront convention center in hopes of attracting more and larger conventions and trade shows.

When the issue was placed before local voters in 2020, they were told that it required a two-thirds vote. It received 65.2% of the vote and election officials declared it a loser, but the San Diego City Council nevertheless voted to say it passed.

Tax increase opponents sued, alleging that while the measure was placed on the ballot by initiative petition, it was a sham that concealed the role that officialdom played in the process. It resulted in last week’s appellate court ruling that the tax increase is valid.

Tax opponents may take the issue to the state Supreme Court, but their chances of winning seem slim. Meanwhile, however, the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association is promoting a potential measure for the 2026 ballot that would reinstate the two-thirds vote for local special taxes, regardless of how they made the ballot.

“The Upland loophole has allowed special interest groups to write initiatives that raise taxes, direct the money to themselves, and pass them with just a simple majority,” the organization’s president Jon Coupal said.

Dan Walters is a CalMatters columnist.