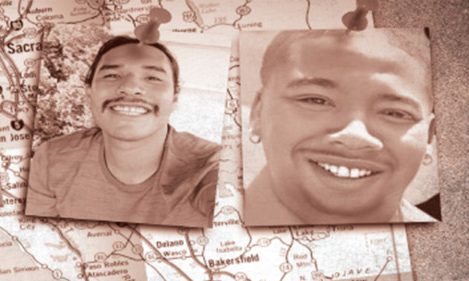

Rosalind Savoid and her son Emmanuel Mitchell (Courtesy Savoid)

It’s something no mother, anywhere, should ever have to hear: A recording of the 911 call from the sober home, after her son’s body was found on the bathroom floor.

“This guy has no pulse,” the woman caller says. “He’s not awake. We tried to shake him… no pulse, no response.”

“Overdose?” the dispatcher asks, instructing her to place him on the floor, flat on his back, and start CPR.

“I’m trying to figure out how to use the Narcan, but I don’t know how to use it,” yells a man in the background.

“Keep doing the chest compressions, one two three four five, one two three four five, keep going, don’t stop,” the dispatcher says. “Do you know what kind of drugs he does?”

“We’re a sober living house,” the woman says.

You can almost hear the dispatcher sigh. The man finds Narcan. The dispatcher explains how to use it. But nothing happens. After about seven minutes — and two more rounds of Narcan — the wail of sirens are finally heard. Another dispatcher comes on the line. The first one shares the address on Normandie Avenue in Los Angeles. “Sober living house,” the first dispatcher says. “But possibly not sober today.”

Emmanuel Deron Mitchell, 28, was recruited to Los Angeles from Oklahoma on Jan. 2, 2024, by the addiction treatment empire linked to Nathan Young, who faces myriad lawsuits in state and federal court. Mitchell struggled with Percocet but was intent on finally getting well. “He was saying he wanted to make a difference,” his mom, Rosalind Savoid, said. ” He said, ‘I want to beat this so I can help other people for real.’ “

Rosalind Savoid and her son Emmanuel Mitchell (Courtesy Savoid)

But addiction is a powerful beast. Barely five weeks later — at 6:30 p.m. on Feb. 7, 2024, at the sober home where he was supposed to be recovering — Mitchell was pronounced dead. “Taxological exam shows the presence of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which can cause severe respiratory depression, coma and death,” the coroner concluded.

A civil complaint filed by Savoid on behalf of Mitchell’s child — against Young (aka Pablo Lopez), more than a half-dozen treatment homes, Dr. Jiseung Yoon, and others — asserts negligence, neglect and abandonment, as providers failed on multiple fronts to provide basic standards of care.

“No one knew how to use Narcan,” Savoid said softly. “How is this a sober home and no one knew how to use Narcan?”

Assertions of substandard care are painfully echoed in yet another complaint against Young and co., filed recently by Cathy Ann Santos on behalf of the five children she shared with Benjamin Barragan.

‘Rampant drug use’

Native Americans have generous insurance benefits via the federal government. Because of that, they are prized by private-pay rehab operators.

Memorial booklet for Benjamin Barragan

Barragan, 29, was a tribal member of Spirit Lake Reservation of North Dakota. He was struggling with substance use, even while caring for his five kids and closing in on a college degree in natural resource management. In April, 2024, he was recruited for treatment to the Young empire here in California.

After accepting a plane ticket and coming to L.A., he was told there was an issue with his insurance, the complaint said. He was “inexplicably” thrown out on the streets. After a few days, the insurance issues were apparently cleared up and he went to a residential treatment home, not the detox center that had been promised. He was “surrounded by rampant drug use” at an overcrowded house where, according to the complaint, “house managers sold drugs and acted like prison guards.”

Related Articles

One-time California drug rehab mogul faces federal criminal charges

Pittsburg to overhaul policies curbing underage consumption of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis

California OK millions for 19 new Bay Area addiction and mental health treatment centers

Why do Bay Area homeless people turn down shelter beds?

Nearly a quarter of people on long-acting opioids develop addiction

Food was scarce, no meals were prepared, no support staff monitored him to prevent relapse. “He was forced to participate on a Zoom program 7 hours per day which did not relate to his fentanyl addiction or recovery,” the complaint said. “Instead, as he spiraled, Barragan was ignored.”

Benjamin Barragan and his children (Courtesy Barragan family)

Without proper treatment, Barragan relapsed, it said. On June 13, 2024, he died alone, of a fentanyl overdose, in the bathroom. “Although time of death was determined to be midnight, Defendants’ staff failed to search or find Benjamin until 6 a.m. the next morning,” the complaint said.

Barragan’s family didn’t learn of his passing for more than a week, Santos said.

“It breaks my heart he went to there to get better and that’s how he died,” she said, weeping. “He was a great father. He was the one raising them. I’m not going to stop ’til I get justice for my Benjamin and my kids — ’til I stop anybody from coming to this state.”

Neither Young nor his attorneys responded to requests for comment on the latest complaints, which come in the wake of a string of headaches.

Young’s network of treatment facilities and sober homes began to crumble late last year, after insurers stopped paying and several state licenses were revoked. He weaponized addiction for profit, insurance giant Aetna charged in a $40 million federal lawsuit, asserting that his businesses cycled patients from one entity to another and encouraged relapse so billing cycles could start anew. Young countersued Aetna, asserting that the insurer greedily endangered addicts’ lives by cutting treatment short and indefinitely delaying payments.

Young has said that his intention has always been to help people, especially those on the lowest rungs of society’s ladder, who are overlooked by others.

Benjamin Barragan and his children (Courtesy Barragan family)

More than their deaths

Barragan and Mitchell were real people. They were fathers. They were sons. They were loved.

Barragan was an accomplished athlete and distance runner who held multiple jobs and made his kids a priority, Santos said. He graduated from Minnewaukan High School and was close to finishing at Cankdeska Cikana Community College, eager to get a better job to support his growing family.

He took pride in his cultural identity, traveling with family to treaty council meetings, interacting with tribal and spiritual leaders, “aware of his ancestral lineage from his maternal and paternal families both richly steeped in centuries of Indigenous culture, spirituality and identity,” his memorial program said.

“He thought the world of his kids,” Santos said.

“And they didn’t even give us an opportunity to say goodbye.”

Mitchell, meanwhile, was a brainy kid. He started reading at age 3, excelled in school, loved football and basketball and boxing. But his greatest talent was how he could take apart any machine and put it back together again.

Emmanuel Mitchell and his daughter (Courtesy Rosalind Savoid)

“He was my IT department,” Savoid said. He worked with her at her day care center in Oklahoma, and excelled at sales and customer service jobs, where his warmth could instantly put people at ease.

“On the outside, he was one of the happiest people,” she said. “He always had smile and joy for you, even if he wasn’t in that state himself.”

Mitchell struggled with Percocet, and after some stints in sub-par rehabs, figured out the jig. “Mama, these people are making $20,000 to $25,000 per head,” he told her. He vowed to kick his addiction in California, come back home healthy, and open a rehab with integrity that would truly help people. “We’re going to do it the right way,” Mitchell told Savoid. “We’re going to be the first real one in Oklahoma.”

Relapse risk

Savoid knows she’s not responsible for what happened, but it’s hard not to feel guilty. Mitchell was nervous about coming to California, but he was ready to truly recover, and Savoid stood back and let him make those choices. She wishes she had come with him, investigated, intervened…. An extra heavy burden to bear atop an already unbearable one.

Rosalind Savoid and her son Emmanuel Mitchell (Courtesy Savoid)

The programs failed to medically assess Mitchell’s level of drug use, or the level of care required, before admitting him for an unusually long 30 days in intensive detox, the complaint said. Then, though he was at a high risk of relapse, suffered from depression and had significant apprehension about leaving detox, he was “stepped down” to a house without behavioral health staffers, with no continuity of care, the complaint said.

Yoon, the doctor providing “incidental medical services,” spent “only minutes on a zoom/telemedicine appointment with limited information,” failed to make sure that all psychiatric and medical issues were addressed concurrently, and “opted to facilitate the misuse of virtual telemedicine appointments and group sessions involving sometimes in excess of 490 people in a group,” rather than involving Mitchell’s family or a close support network in real therapy, the complaint said.

Savoid vowed her son’s death will not be in vain. She’s working on setting up a foundation in his memory, to bring his hope for recovery with true integrity to life. “His heart was to help people,” she said, “even though he needed help.”

Defendants in the Savoid complaint include 33rd Street Detox, Healing Path Recovery, Healing Path Detox, The Kiloby Center for Recovery, Antioch Rehab, Elmo Detox, Cameron Park Rehab, Young, David Young (aka Sancho Lopez), Yoon and 55 Silver.

Defendants in the Santos complaint include Antioch Rehab, A New Start Treatment and Recovery, Kiloby Center For Recovery, Cameron Park Rehab, Commonwealth Rehab, Auburn Rehab, Clear Skies, Beach Street Rehab, Healing Path Recovery, both Youngs and 55 Silver.

Avalanche of litigation

Karen Gold is the attorney for both these families, as well as for several others who say they suffered in this treatment network. Gold has also filed more than 60 claims on behalf of victims who said they suffered injuries and damages.

“I am receiving calls and emails almost daily from victims of Nathan Young related corporations,” Gold said by email. “I will continue to bring claims and cases on behalf of these victims because the pattern of behavior has not changed. People continue to be heavily recruited from states like Florida, Hawaii, Oklahoma, North Dakota, North Carolina, Alabama, Pennsylvania, Georgia and Texas. Once insurance arranged for them runs out, they are dropped off at dangerous homeless encampments if they can’t get a plane ticket home….

“No steps are taken to provide continuity of care or provide information for public-assisted drug detox and treatment or other homeless services. To me these people are seen as disposable and tossed out like garbage once health insurance runs out. In all my years of handling these cases I have never seen such a callous disregard for human suffering or life.”