Despite the financial stress of Golden State life, Californians are relatively good at paying bills compared with the rest of the nation.

Take student loans. In the first quarter of 2025, 18% of California student loans were late.

Related Articles

Special education students at CSU East Bay denied commencement walk

Older people in crosshairs as government restarts Social Security garnishment on student loans

Here are the winners and losers in the Republican tax bill

Stanford declines to discuss Israeli divestment as hunger strike protestors vow to grow numbers

San Jose State University beats Stanford, Cal in computer coding

That may seem like a stunningly high rate of skipped payments, but it’s the 10th lowest delinquency rate among the states and the District of Columbia. And across the nation, 23% of student loans were delinquent.

That’s what was found by my trusty spreadsheet’s review of bill-payment data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The research, from 2003 to the first quarter of 2025, examines debt levels and payments drawn from individuals with credit histories.

The latest report was the first since student-loan repayment reprieves ended. That means late payments on many educational loans were once again being reported to credit bureaus. This provides a window into the scope of this education-linked financial challenge.

Student loans are roughly 5% of all California debts. These borrowings equal $4,660 per capita of the $87,620 total consumer borrowings statewide.

Nationally, it’s a bigger hurdle: student loans run $5,470 per capita – or 9% of Americans’ $62,490 per capita debts.

The ability to pay varies wildly. Mississippi was the worst at student-loan repayment, with 45% of these debts in arrears, followed by Alabama, Wisconsin, Kentucky, and Oklahoma, all at 34%.

The best at making payments lived in Illinois and Massachusetts, with 14% delinquency, followed by Connecticut, Virginia and New Hampshire were next at 15%.

Bigger picture

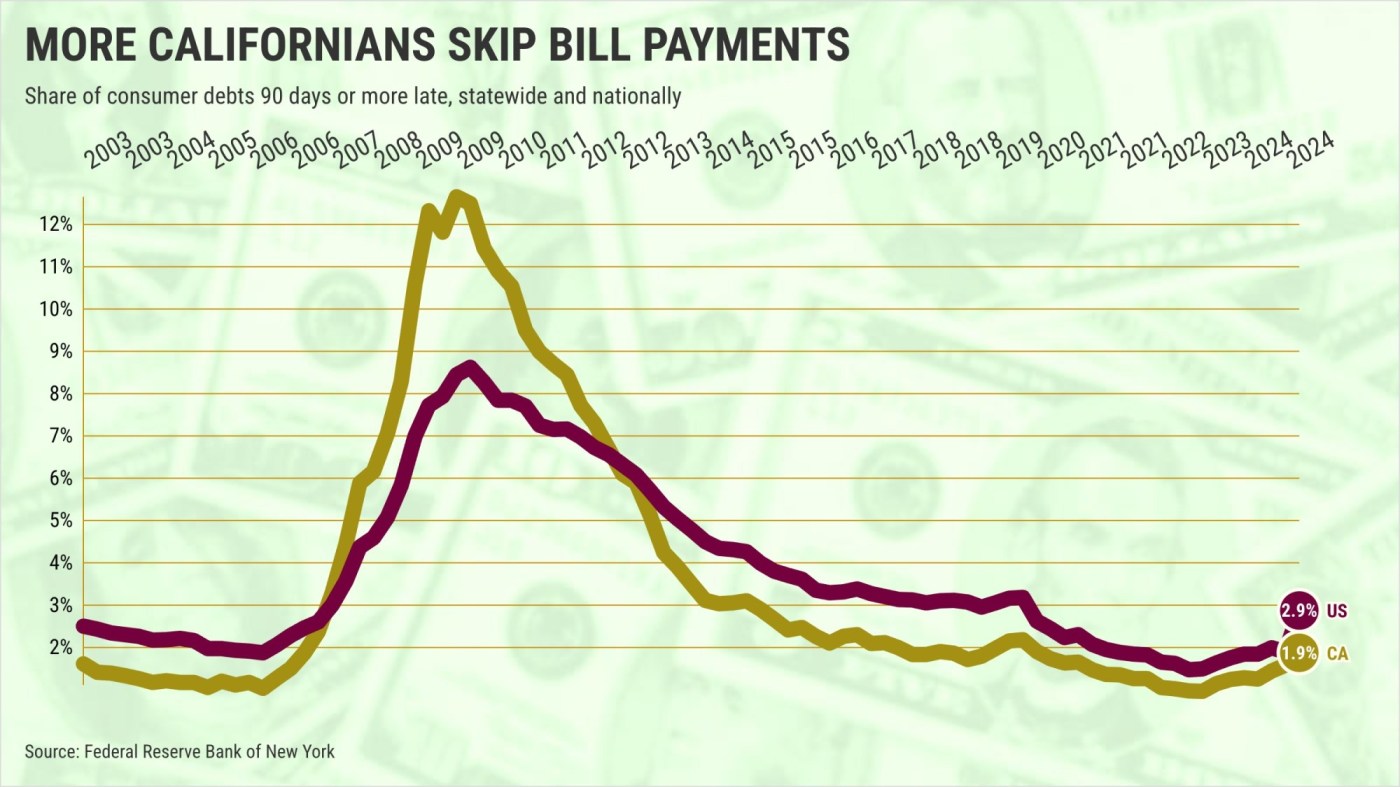

To start 2025, only 1.9% of all California consumer debts were 90 days or more past due.

Yes, skipped bills increased from 1.6% at year-end 2024. And it’s California’s highest level of tardy bills since the second quarter of 2020, when coronavirus lockdowns severely impacted the economy.

However, this level of delinquency is significantly lower than the 3.6% average lateness since 2003.

Nationally, 2.9% of bills were late in the first quarter, up from 1.9% at year’s end. Like California, the rate is still historically low. American tardiness has averaged 3.8% during the last 22 years.

California’s economy also has its challenges. Job creation has slowed to a crawl. The state remains unaffordable for the masses. The Trump administration’s “America First” thinking collides with California’s globally oriented business climate. Consumer confidence is also down.

That monetary angst can be found in the slowdown in Californians taking on new debts.

In the first quarter, total borrowings increased at an annual rate of only 0.8%. That’s well below the 3.3% growth pace since 2003.

It’s a similar picture across the nation. Borrowings are up 1% in a year vs. a 3.3% average growth.

Home sweet home

The New York Fed tells us Californians are getting better with home loans, which are 81% of all consumer debts statewide.

Just 0.56% of mortgage balances were 90 days or more late to start 2025. That’s down from 0.58% at year’s end. Although we’ll note that the late mortgage level in the fourth quarter of 2024 was the highest since the second quarter of 2020.

And lateness is historically low – below the average 2.8% late home loans since 2003.

Equally noteworthy is that California’s improvement rate comes as more Americans fail to make timely payments on mortgages, which are 70% of all U.S. consumer debts.

In the first quarter, 0.9% of U.S. home loans were late – the worst payment pace in five years. That’s up from 0.6% at year’s end, but this is still comfortably below the 2.6% historical norm.

There is a rising level of deeply troubled homeowners.

California had 15 new foreclosures per 1,000 consumers in the first quarter. That’s the highest since the first quarter of 2020 and up from 12 at year’s end. But to be fair, it’s also nowhere near the 88 per 1,000 average since 2003.

Same story nationally with 21 U.S. foreclosure starts per 1,000 consumers – up from 14 at year’s end but off the 70 historic pace.

Jonathan Lansner is the business columnist for the Southern California News Group. He can be reached at [email protected]